This post originally appeared on tBL member SCGWest’s blog and is republished with permission. Find out how to syndicate your content with theBrokerList.

Zoning and land use issues can be confusing, especially when you hear terms that are related but different. Do you find yourself getting confused about the difference between rezoning, conditional use permits, and zoning variance? Want to know what each of these processes entails?

In this article we’ll look at the differences between rezoning, conditional use permits, and zoning variances, and give some examples of when you would use them.

But first, let’s start with a little refresher on how zoning works.

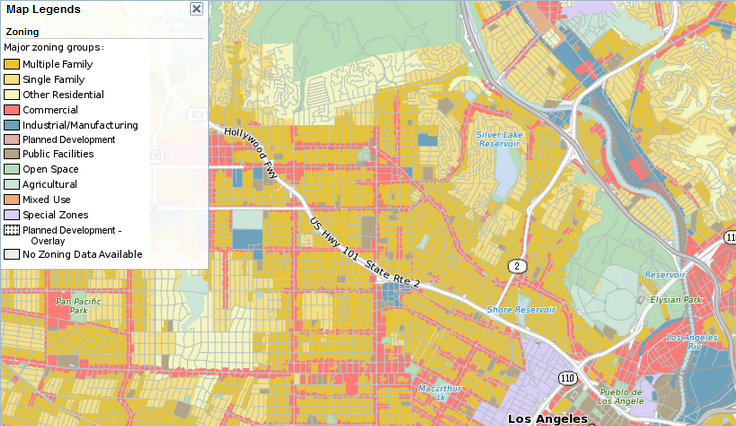

Each municipality has its own zoning laws that dictate how the land within its boundaries can be used. Essentially, the land within each municipality is split up into different use categories, such as residential, commercial, industrial, and agricultural. Zoning laws go deeper than that though – they also dictate things like how tall a building can be, how much parking is required, or even whether you can build a garage behind your house.

Cities and other municipalities enact zoning laws to keep conflicting land uses away from each other, and to encourage growth in the way that they feel is best. So, for example, nobody wants to live next to a noisy or smelly manufacturing plant, so housing and industrial areas are kept separate in zoning maps.

In other areas, it’s not quite as clear cut, and there may be residential and commercially zoned parcels of land very near each other.

Rezoning, conditional use permits, and zoning variances come into play when someone (a real estate developer, a business owner, or a homeowner) wants to do something that is different from what the zoning laws allow. Sometimes that can mean changing the land use entirely, and other times it can mean asking for an exception to a relatively minor detail within the zoning law.

Rezoning

Rezoning involves completely changing the designated land use from one category to another. A change from agricultural to residential would involve rezoning the land, as would changing from residential to commercial.

Rezoning can be a lengthy and complicated process. The process varies according to which municipality you’re in, but generally you’ll need to start with the planning commission in your city. If they approve, the city council will usually need to pass legislation to make the change (but in some municipalities, the planning commission’s approval is sufficient).

Here are some of the things you’ll have to do if you’re trying to get a property rezoned:

- Have a preliminary meeting with the planning commission

If the planning commission in your city will do a preliminary meeting, it’s best to take advantage of that and talk with them about your plans before you do a formal application. You may get some information that will help you submit a better application, or you may find out that your rezoning request has little chance of being approved. Either way, you’re likely to get valuable information.

- Talk with surrounding property owners and the community

Plenty of rezoning requests have been denied because the community was against them. Talking to the neighbors, addressing their concerns, and helping them understand your plans for the land will go a long way in helping the approval process. In fact, there will probably be at least one public meeting as part of the application and approval process.

- Submit a formal application and pay the application fee

- Attend a hearing with the planning commission

There may be more than one hearing that you’ll need to attend. You’ll have to make a strong case for why the property should be rezoned, so you’ll need to spend significant time preparing and doing your research. If the planning commission requests changes to your application or proposal, you’ll probably have to go back in front of them.

- If the planning commission is in favor of your zoning application, you’ll probably have to attend a city council meeting and speak publicly about your plans as well as answer questions. In most municipalities it’s the city council that will ultimately decide, so this is another time when you’ll need to be very well prepared.

Rezoning a property isn’t always difficult. Some municipalities recognize that their zoning laws are out-of-date and are no longer serving the community well. For example, in cities that want to promote housing construction, it can be fairly easy to get land rezoned from agricultural use to residential to allow a developer to build a housing subdivision.

Conditional use permits

Within a city’s zoning laws, there are usually “conditional uses” that are identified in some of the zoning categories. Conditional uses are uses that may be permitted as long as the city’s requirements (or “conditions”) are met.

It’s easier to understand conditional use permits by looking at an example: In many cities, areas that are zoned for residential use will have a clause in the zoning law that says that K-12 schools or churches are a conditional use – that is, they are seen as compatible with the residential category and will be permitted, subject to the city’s approval.

Conditional uses aren’t automatically approved – the city will still want to make sure that the proposed development is built in a way that’s compatible with the rest of the area. But they don’t require rezoning.

Conditional use permits can only be used if the proposed use is specifically permitted in the zoning law.

The process is similar to rezoning, but usually simpler. You’ll still have to go through your city’s planning commission and submit an application. In most cases, since the proposed use is specifically permitted by law, conditional use permits have less potential to be controversial (although the planning commission may still request changes and tweaks to your development to address community concerns).

Zoning variances

Zoning variances are used when a proposed development is requesting an exception to some portion of the zoning law. A variance may sound similar to rezoning, but it does not involve changing the zoning law the way that rezoning does – it’s more of an approved exception to the existing zoning law.

Here’s an example that may help clarify this:

If a developer is proposing to build a commercial development on land that’s zoned for commercial use, it may seem at first glance that they’re in compliance with the zoning law. But, remember, the zoning law also covers things like building height, density, setbacks, and parking requirements. So, as an example, if the city’s zoning law limits new buildings to 60’ in height and the developer is proposing a building that’s 65’ tall, the developer would need to request a variance – an exception to that part of the zoning law.

When a zoning variance covers building height, density, setbacks, or parking, it’s referred to as an “area variance.” There is also something called a “use variance,” which changes the permitted use of the property (e.g., if an area is zoned for retail stores and someone wants to locate a dentist’s office there, that would require a “use variance.”)

Area variances are much more common. Some municipalities don’t even allow use variances, and in that case, changing the use of the land would require rezoning or a conditional use permit (if applicable).

Why would a zoning variance be granted? The landowner or proposed developer would need to show that strictly applying the zoning law to the property would cause them “unnecessary hardship.” Usually, that means that there’s some peculiar characteristic of the property that differentiates it from adjacent properties, and thus prevents the owner from enjoying the same use of the property that the adjacent property owners enjoy.

However, municipalities can and do grant variances if they feel that the variance will result in a better project that aligns with the city’s goals. For example, variances are sometimes granted allowing for more apartment units to be built than the zoning law would normally allow. A city may grant that variance because their goal for the area is denser, walkable housing – and more units in a particular development would contribute to that goal.

Zoning variances are usually handled by a Board of Zoning Appeals or a Board of Zoning Adjustments (there may be a different name in your municipality). It depends on the municipality whether or not the BZA has the power to approve or deny requests, or whether that decision has to be made by the city council.

ᔓ

Rezoning, conditional use permits, and zoning variances are complex, and you should always consult with experts if you’re thinking about applying for one of them for a property you own or are considering purchasing.