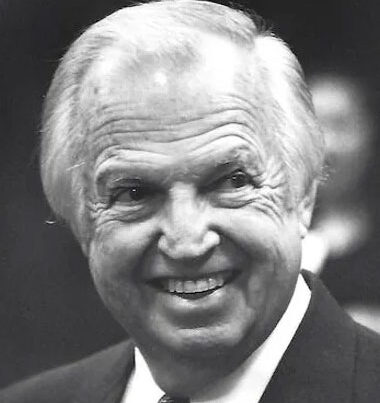

New York City–based Jonathan Rose Companies founder and affordable communities pioneer to receive prestigious ULI Prize for Visionaries in Urban Development.

ULI Prize for Visionaries in Urban Development honoree Jonathan F.P. Rose.

Longtime ULI Trustee Jonathan F.P. Rose, one of the real estate industry’s most respected champions of inclusive, equitable, and sustainable community building, has been selected as the 2021 recipient of the Institute’s highest honor—the ULI Prize for Visionaries in Urban Development. The prize spotlights individuals and organizations that employ innovative processes, techniques, strategies, and insights to achieve the highest quality in development practices and policies at the global, national, or local level. It rewards accomplishments that honor diversity of land use, design, mobility, lifestyle, population, culture, and race.

Rose is the president and founder of New York City–based Jonathan Rose Companies, a multi-disciplinary real estate development, planning, and investment firm that focuses on creating affordable, transit-accessible communities that are culturally and socially diverse, environmentally conscious, and economically prosperous. The company, which Rose founded in 1989, has developed, acquired and redeveloped, or preserved more than 100 mixed-income, multiuse developments throughout the United States, often in partnership with nonprofit organizations, for-profit firms, and housing agencies. All of Jonathan Rose Companies’ work emphasizes regenerating the fabric of communities by creating communities of opportunity with the aspiration that every resident and employee has equal access to opportunity, environmental quality, health, and well-being.

Prize jury chairman and ULI Trustee Leslie Woo calls Rose a “true ally” in the quest to create more inclusive cities, in that his decades-long commitment remains steadfast. “He saw the need [for equitable, sustainable communities] long before most in the industry, and he has constantly addressed it through his work,” says Woo, chief executive officer of CivicAction, a civic engagement organization in Toronto. “Even with all of his accomplishments, Jonathan continues to evolve, striving to make a difference and raise the bar for himself and all of us.”

Acclaimed architect and urban planner Peter Calthorpe, the 2006 winner of the ULI Prize for Visionaries, has known Rose for more than 40 years. Calthorpe has collaborated with Rose, who is also his brother-in-law, on numerous projects. “The ethics Jonathan lives by are about his respect for history, community, people, and the environment,” says Calthorpe, senior vice president at HDR/Calthorpe in Berkeley, California. “He does not see these as being separate—he sees them as part of one system of values based on the premise that if you take care of people, you take care of the environment, and if you take care of the environment, you take care of people.”

Rose has contributed to several publications on sustainable development. His book, The Well-Tempered City: What Modern Science, Ancient Civilizations, and Human Nature Teach Us About the Future of Urban Life, was published in 2017. Rose recently spoke with Urban Land about his holistic approach to building communities of opportunity.

Sendero Verde. (AECOM)

How do you see real estate as a way to pursue your passion for sustainable and equitable cities?

I feel like I was born with a calling. First, growing up in the suburbs of New York City, I was deeply connected to nature. Second, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the civil rights movement became much more prominent, and my mother was deeply involved in voter rights, so the idea of social justice became really important to me. And third, my father was a real estate developer. When I could, I loved going to work with him to see building construction. Ever since the start of my real estate career, I’ve applied my appreciation for nature and social justice to real estate development. It was challenging at first, because I did not have a model for doing that. In the early 1970s, I found inspiration in Jim Rouse, who was developing Columbia, Maryland, at the time—a major undertaking with an environmental, social, and economic mission. His work was so influential to me that I subsequently joined the board of the social enterprise he formed, Enterprise Community Partners, and have remained involved with the organization for decades.

You were advocating for and developing mixed-income, transit-oriented communities early in your career. What prompted this as a priority for you?

I have consistently advocated for creating transit-oriented, mixed-income communities because they are better for families and the environment. Before starting my own company in 1989, I spent 13 years in my family’s business, Rose Associates. Their philosophy, dating back to 1926, was, “Only build within two blocks of a train station or subway line.” As the negative environmental impacts of the automobile became clear, as well as the costs, we made TOD a founding principle of our firm. By 1989, it also became clear that concentrating lower-income residents creates pockets of poverty and does not serve them, their neighbors, or cities well. So we try to create mixed-income communities close to transit and make them green.

When I started building green projects, the affordable housing industry was skeptical—the prevailing assumption was that, with limited public subsidies, spending more to make affordable housing green would produce fewer affordable housing units. So I had to learn how to build green and affordable housing for the same budget as building regular affordable housing. It was a fantastic discipline for me. Eventually, through my connection to Enterprise, I convinced Bart Harvey [former chair and chief executive officer of Enterprise Community Partners and the 2008 recipient of the ULI Prize for Visionaries in Urban Development] that greening made economic sense. That led to the creation of the Enterprise Green Communities program, with standards and guidelines that have transformed the field.

The Denver Dry Goods Company Building. (Jonathan Rose Companies)

In The Well-Tempered City, you state that development from the 1950s tends to be among the least functional in terms of fostering cohesiveness in our cities. What can be learned from this to create better cities today?

In the 1950s, there was a tendency to apply very linear thinking to zoning in America, segregating land uses—office, retail, low-income housing, high-income housing—with a science of efficiency in mind. This also perpetuated racial segregation, which was exacerbated by the location of America’s new highway program. What urbanists have come to realize is that for cities to really thrive, they need to weave all their elements together, increasing connected diversity.

[From] 1991 to 1992, I developed my first major project, the renovation of the Denver Dry Goods Building into a mixed-income, mixed-use, green, historic preservation community next to a light-rail stop. Other developers had tried turning the property into single uses such as all retail or housing, and none of that had worked. I proposed placing all the elements desired for downtown office, retail, for-sale condos, affordable apartments, market-rate rentals into one building. The project thrived, and it became a seed for turning around downtown Denver. The theory of integration worked.To achieve this required extensive collaboration among public officials and other stakeholders. Denver was in a slump at the time. The revitalization of this beloved building at the city core inspired the many agencies, banks, investors, and the 40 lawyers who represented them to work together to make the project succeed. Cities will always have challenges—environmental, social, economic, and racial. Optimizing the common good rather than maximizing the self-good is how we solve these issues. The collaboration to get the Denver Dry Goods Building redeveloped was a model of that [approach].

East Harlem Center for Living & Learning. (Paul Rivera)

You have developed highly acclaimed affordable, equitable, and sustainable communities in New York City and throughout the United States. How do you know when you get development right?

First, with any project, I want to learn something new, developing an idea that my company has not done before while building on the best we have achieved. Every project is a progression of a continuous learning-and-doing cycle. We get it right when the lives of our residents are improved and we have reduced our environmental impact. And the projects have to be economically successful. Creating successful models that others will duplicate is key to expanding our impact. Projects that don’t work financially are unlikely to be duplicated.

Our projects aim to—at a minimum—meet Enterprise Green Communities standards, and we are constantly raising our greening goals for our developments. We are also increasing our goals for achieving communities of opportunity, which is our integration of social, health, and education goals for our residents, and putting those resources into our projects. We do this in a co-creation process. The development is better when the residents are our partners in its vision and success.

Co-creation of communities involves much more than building places for people to live. What goes into creating a true community of opportunity?

Clearly, affordable housing is a platform for opportunity. And making affordable housing safe and green is really important, because we have learned so much about the negative effects of the environmental toxins that often affect the health of families living in lower-income housing. All our projects have a complement of services related to the mental and physical well-being of our residents. We provide health exam rooms and partner with local health agencies to have physicians and nurses see residents at our properties. We provide computer rooms so residents have online access. We partner with local youth organizations to provide after-school programs. We offer access to community vegetable gardens, and we try to partner with local groceries and food banks to offer healthy and affordable food to our residents, and we provide a voter registration program for residents.

All of this is laid out in our community-of-opportunity toolkit, with services supported by a resident service coordinator. While doing this is more challenging than just building affordable housing, building communities of opportunity can accomplish so much more in terms of supporting the lives of our residents.

Your company has launched major investment funds to help preserve affordable housing in several cities and make the housing greener and more energy efficient. What have you learned from these initiatives that inspires you to keep doing this?

In 2020, we closed on a $525 million affordable housing preservation fund, our fifth such fund. The United States is losing 120,000 units of affordable housing a year. Their preservation is essential, and these funds provide us with a strong tool for that. Our investors include health care and education endowments, foundations, pension funds, and high-net-worth individuals who are seeking excellent risk-adjusted returns as well as social and environmental impact. We combine this equity with Fannie, Freddie, or Federal Housing Administration debt to purchase existing affordable housing that may be at risk for gentrification. We preserve it to stay affordable, make it green, and supplement the housing with community-of-opportunity services.

The buildings we purchase through these funds almost always have low-hanging environmental opportunities. We invest equity in any environmental improvement that has a five-year payback or better—that works out to a 20 percent return on our investment. This includes simple energy-efficient tactics such as installing LED lighting, lots of insulation and weather sealing, and energy-efficient and water-saving appliances. It’s an easy-to-duplicate way to reduce environmental impacts and save money.

In The Well-Tempered City, you write that the purpose of cities is to provide for the protection and prosperity of their residents, to oversee the fair distribution of resources and opportunities, and maintain harmony between humans and natural systems. What distinguishes the cities that are able to do this from the ones that are not?

The cities that come closer to this vision have a long-term vision and a strategic plan for how to achieve it. It is really hard to achieve these goals in one year, four years, or even 10 years. This requires a consistent commitment across city administrations to achieve these goals. Also critical is a sense of civic responsibility among the business and the not-for-profit communities. The citizens need to recognize the preciousness of the commons—the natural commons, the human commons, the social commons, and their shared economy—and recognize that their well-being grows from the commons. To be successful, a city’s culture has to emphasize optimizing the city versus maximizing an individual within it.

Also, it is helpful to reflect the vision in metrics. For example, tracking the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, the affordability of housing, the performance of students in reading and math, and the increase in public safety. These types of metrics can help a city measure progress in achieving its vision and make adjustments to keep on track to deliver the vision.

Via Verde. (David Sundberg/Esto)

What have we learned about city building from the COVID-19 pandemic and the calls for racial justice in 2020?

One result of the 2020 protests was to spotlight the long-term effects of the history of racism in America. It is clear that inequality is still pervasive in America, a result of many decades of racist practices. For example, until the 1970s, it was very hard for African Americans in some cities to obtain mortgages. To buy houses and build home equity, they had to get subcontracts and pay much higher interest rates. What that meant is that African American families with the same education level and income as white families were not able to save and accumulate equity to help their children and grandchildren get ahead. If our real goal is to equalize the landscape of opportunity, we have to understand how the landscape is unequal and then work assiduously to overcome it.

From the COVID-19 pandemic, we learned how important our essential workers are, and that they deserve fair hours along with fair wages. This category [of workers] includes the frontline employees in the real estate industry. Many employers of essential workers are focused on efficiency and optimizing work hours, with less regard for their employees’ quality of life, such as the time needed to properly raise their kids. Hopefully, the pandemic has underscored our duty of care for the well-being of our essential workers. We have a moral responsibility to protect the mental and family health of our essential workers along with their physical health.

What advice would you give to a young person who wants a meaningful career and is thinking about real estate?

Real estate is a powerful platform for making a difference in the world. It deeply connects to issues of racial and social justice, to issues involving the environment, and to the future of cities and society. Real estate is a very open and flexible platform that not only can absorb your best thinking but also needs your best thinking.

How might ULI be more effective in leading the industry toward more equitable and sustainable design and development?

ULI is an extraordinary center of knowledge, a great platform for distributing the best ideas and emerging ideas to its members. It is a network in which we learn from each other. I have been a member for 36 years, during which ULI has been a constant source of inspiration, information, and companionship. I am grateful to be part of the ULI community and am deeply honored to have been selected to represent ULI’s vision.

Nominations for the annual ULI Prize for Visionaries in Urban Development are open. The nomination form is available, and the deadline to nominate the 2022 laureate is December 31, 2021.

TRISH RIGGS, a public relations consultant and freelance writer with Keadle-Riggs Communications, was a senior vice president with ULI from 2005 to 2019.