Many malls were created with White suburban shoppers in mind. Redeveloping these properties with attention to practical needs of diverse communities can help ameliorate the legacy of racial segregation.

Shopping malls have a special place in the popular culture of the United States. For younger baby boomers, gen Xers, and older millennials, the mall served as a town square of their childhood. And even as malls falter, the retail sector has reflected massive prosperity for over a century, now with over 8.5 billion square feet (790 million sq m) of space dedicated to sales and storage, circulation, and services for moving manufactured goods.

But while this growth mirrors the social and political rise of cities, to the benefit of affluent White families, it has largely left a void for racial minorities and less-affluent White people. In too many cases, mall growth resulted in fewer resources, less opportunity, and a landscape in need of healing, both ecologically and spiritually. The story of retail real estate is inseparable from the human struggle for equality and inclusion.

As these mall assets become defunct, they open the door to improved designs—designs that may finally incorporate equity and even address issues such as climate change and the stagnating middle class.

How Malls Mirrored Inequities

The examples of systemic racism influencing land use are rampant. Houston, for example, was organized by a radiating geography of racially segregated, numerical wards. Instituted in 1837 to organize council districts, these land use patterns persisted well into the 21st century, sweeping up retail planning and development along the way.

“Following the Civil War, emancipated Black families lived in Fifth Ward, Third Ward, and the southwestern section of Fourth Ward,” Janet Wagner wrote in January 2012 for Houston History magazine. Most of the city’s malls—along with city parks and new suburban development—followed the outlines of the mainly White First and Sixth wards well into the suburban reaches.

Nationwide, redlining codified inequities. Starting with the Federal Housing Administration in 1937, the practice mirrored retail development in carving racially drawn ghettos, often reinforcing biases and accelerating the decline of basic services and unmet daily needs for communities of color.

Indeed, unhealthy development severely harmed these communities. An overlay of the University of Virginia Demographics Research Group’s racial dot map on almost any U.S. city shows a strong correlation between communities of color and proximity to sewage treatment plants, industrial uses, and other hazardous land. An overlay of this racial map with shopping malls reveals an almost exact tracing of White flight and the developer-friendly residue of redlining.

Compounding the depreciation and stigmatization of inner cities, this institutionalized racism and classism incentivized suburban housing, commercial development, and infrastructure farther and farther from city centers. Accelerating all this destructive segregation was federal highway construction: it plowed through underprivileged neighborhoods, separating them from the success of privileged—largely White—residents.

De-Malling through Demography and Design

Malls have a particular story to tell. Today, their design limitations have turned them into white elephants on the urban landscape. Department stores’ reciprocal easement agreements, shared common-area maintenance costs, and a pizza pie of ownership slices have made these defects glaring.

It is past time to examine how distribution of malls—and other retail development such as grocery stores—has exacerbated inequity. Inner-ring suburban malls are among the most blighted. They mirror the segmented and uneven prosperity of their host cities, especially as immigrant and minority families have formed communities in the wake of departing White families. The resulting communities lack sufficient retail resources to fully serve the remaining residents.

By design, few of these centers were intended to serve constituencies other than relatively wealthy Whites. Most of these malls lacked access to mass transit, limiting access for potential inner-city shoppers. And rarely did they have community services on site. They were designed predominantly by White men predominantly for White women to consume disposable goods with their disposable incomes.

Following White flight, these malls suffered from this lack of mass transit and insufficient community amenities—a state that has persisted since the 1960s. These factors and others, including the rise of e-commerce and the COVID-19 pandemic, led to the fall of malls.

And yet, for the multicultural communities inheriting these developments in their neighborhoods, there is an upside to this decline.

Serendipitously, inner-ring suburban malls have helped shape some of America’s most racially and economically diverse neighborhoods. These mall neighborhoods, once redeveloped, hold the promise of homeownership, small-business generation, decent public education, and easy access to infrastructure. They may represent the greatest opportunity for integrated, diverse, and equitable communities since the failure of “40 acres and a mule”—the aborted promise of land distribution to emancipated slaves—more than 150 years ago.

Many faltering malls have aggressive plans to densify by adding badly needed housing stock. Where once seas of parking were connected by a ring road independent of municipal thoroughfares, now mall after mall is divided into rectangular blocks or wedges of so-called five-over-two housing stock—five levels of wood-framed housing over concrete podiums. BelMar in inner-ring suburban Denver, Alderwood in suburban Seattle, and Cumberland Mall just inside Atlanta’s perimeter freeway are examples of such housing redevelopment.

But there is a problem: are these developments—discrete neighborhoods with hard external edges and little relationship to the adjacent community—re-creating the ward system that plagued regional malls? Treating the land banks of former suburban malls as more acreage to be divvied up and sold in two-acre (0.8 ha) parcels only increases the likelihood of a jarring and disjointed urban form in the middle of a forever changed suburban America.

Ellen Dunham Jones, an authority on sustainable suburban development, describes this regressive result perfectly: “If you’ve got a grid, more or less, with small, walkable-sized blocks, that’s urban form,” she said in an interview earlier this year with Mother-board. “If you have a highway leading off into cul-de-sacs, that’s suburban form, which is a more treelike kind of pattern.”

A Third Way

Speaking of another period of radical change, Abraham Lincoln said, “The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, we must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has shaken the real estate development world. Vacant single-use retail and entertainment sites have ripped holes in the fabric of suburbs. Prioritizing community benefits and restoration of natural habitats would significantly improve the design strategies for these sites. Urban edges combined with suburban density and a dose of neo-rural landscape might create a new hybrid of American urban form to tackle the issues of diversity, equity, inclusion (DEI), as well as climate change and the stagnating growth of the middle class.

Imagine vocational and higher-education institutions, a significant amount of open space, climate change amelioration, and workforce and affordable housing—all designed for these new communities rather than for the privileged suburbs of the past. Imagine also bridge housing for formerly unhoused individuals plus market-rate stock and space for daycare, senior care, food production, energy generation, performing and visual arts, offices, warehouses, and retail—all on a suburban mall site. Public officials, financial institutions, and private developers can benefit from a deep understanding of place and the demographics surrounding these properties—helping bring about a new framework for growth rather than continuing to employ tired formulas that re-create mall obsolescence.

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Long Beach, California–based design firm RDC created a tactical working group (code name: Rebirth) to design and test mall redevelopment strategies “disenthralled” with the obvious and standard solutions that may only perpetuate existing impediments to DEI. Among the goals of this effort was a balanced approach that rested on several conceptual pillars.

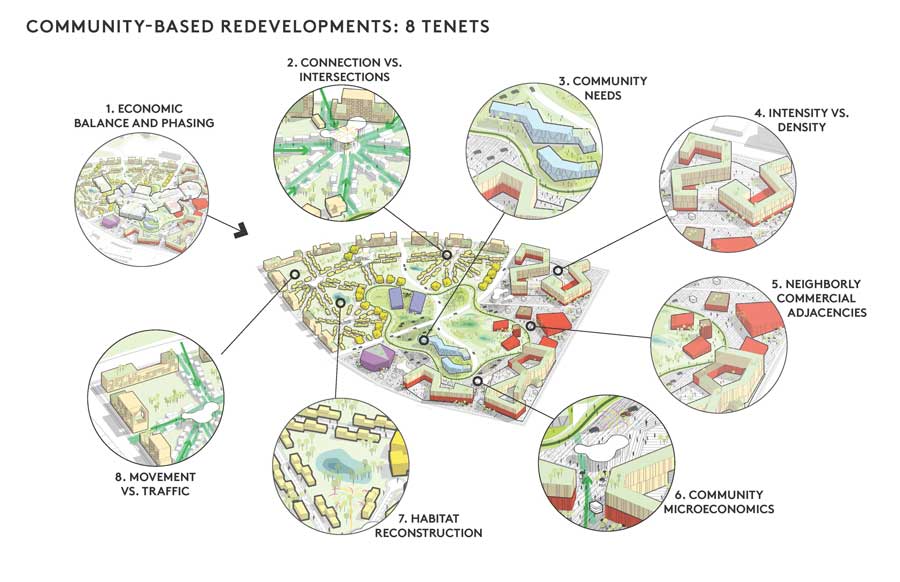

RDC believes inner-ring suburban mall redevelopment should consider eight design tenets:

- Economic balance and phasing. Balancing economic realities of recurring retail revenue and phased redevelopment involves pro forma gut checks at every major design decision. Even a half-empty mall generates shareholder or landlord cash flow. Decisions regarding delayed demolition or phased relocation of existing retailers must be made with great care. Test and repeat.

- Connections versus intersections. Valuing connections over intersections, especially emphasizing pedestrians over cars, reduces the automobile footprint by connecting nodes of activity rather than creating redundant intersections that impede pedestrian pathways. This approach prioritizes human interaction in order to create equitable common areas that appeal to a diverse assortment of users.

- Community needs. Designing for a local population’s daily needs instead of a generic mall shopper requires a deep understanding of the people who are living near the mall. And creating amenities to attract diverse residents from surrounding communities can create critical mass. Social media, user interviews, and multigenerational and multiracial focus groups can all help create representative development.

- Intensity versus density. Emphasis of intensity over density does not imply a diffuse development. RDC’s research validated the use of woonerfs—“living streets” that, instead of just channeling vehicles, create multiuse social spaces with structured grass surfaces and permeable pavement. This approach also emphasizes radial connections (extending from the center), community reuse of interior assets, and sensitively scaled housing at the edges. The raw numbers of residential units, retail outlets, and community-facing services fit better in this scheme than in the city-block diagram. This allows for intense development at key nodes, balanced with sizable areas of open space, allowing room for the community to thrive and grow.

- Neighborly commercial adjacencies. Creating urban edges that hug neighboring properties instead of towering above them or creating buffers against them acknowledges the nature of American cities. The new development can inspire incremental change on surrounding properties. It should never create jarring or foreign adjacencies. Think of it as a handshake with neighboring uses.

- Community microeconomics. Focusing on the microeconomics of design decisions rather than on traditional delivery methods involves creative public and private financing. That, combined with smart design and a dedication to net-zero energy strategies, can create long-term value. Opportunity zones, subsidized housing, and federal, state, and local grants, as well as institutional partners, all add layers of complication, but they also create more diversified and stabilized developments. If malls previously created a local retail economy, the rebirth of these mall sites should create actual sustainable microeconomies geared toward nearby communities.

- Habitat reconstruction. Preserving pockets of habitat by restoring untamed landscapes creates an entirely new, restored environment and encourages the casual use of the protected, shared fields, marshes, or woods rather than discrete backyards or segregated common areas. Over the past 50 years, many original habitats have disappeared and some species have become extinct. Introduction of plants and animals to the backyards of homes will be a hyperlocal and continually evolving improvement. In most cases, this space would be owned by the developer but cared for by the community.

- Movement versus traffic. Prioritizing pedestrian and bike movement over automobile traffic puts the commuter vehicle at the margins, around corners, or in pockets of inactivity rather than blocking a neighborhood’s human energy. Parking has long been a development driver, but parking ratios have been falling as cities emphasize pedestrian and mass-transit mobility. But what if cars were treated like movable furniture on a site? Permeable pavement, structured grass surfaces, interlocking grids, and other woonerf-style solutions can mix heavy uses (nearly vegetation-free) with slower and lower uses (green space, when not housing automobiles). This approach deemphasizes pavement, curbs, and barriers while slowing cars. The lines separating public and private are blurred.

Where Redesigns Can Work

This “third way” is not without precedent. Raleigh Springs Mall in Memphis, for instance, was razed and replaced with a large retention/recreational lake, police and fire facilities, a skate park, and a new public library. European examples include Vauban, a neighborhood in Freiburg, Germany, that has proved to be a financial and planning success at creating community through sustainable and community-focused design. The Dutch city of Houton began a similarly scaled expansion in the late 1970s and has continued to add tens of thousands of housing units without sacrificing pedestrian primacy and community benefits. On-the-boards examples include Traumhaus Funari, which seeks to redevelop the former Benjamin Franklin barracks at the U.S. Army base in Mannheim, Germany.

The months and years ahead are bound to be both turbulent and triumphant in the journey to a more equitable and diverse society. Mall sites provide lessons of past failures as well as an enormous opportunity to create a movement toward rebirth. Learning from history’s missteps and redirecting priorities toward sustainable and just development will help fulfill the promise of the nation’s founding.

SEAN SLATER is principal of RDC (formerly RDCollaborative), based in San Diego.