(Illustration by Tim Peacock)

This story was originally published in December 2019.

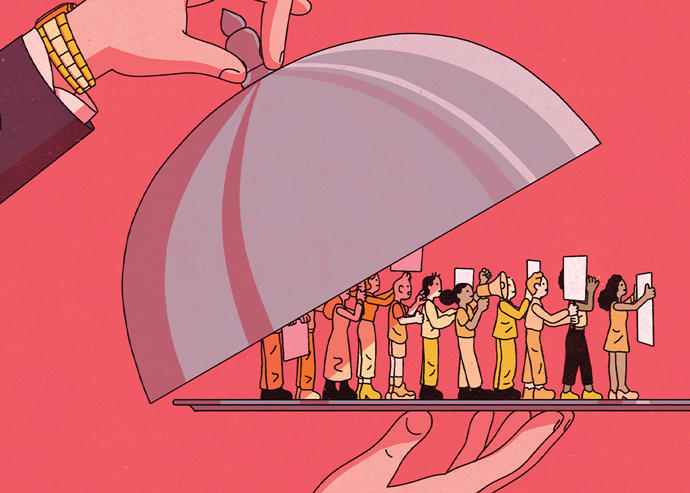

In a small Venezuelan restaurant on a bustling street in Jersey City, a group of people on a stage held placards and homemade signs with a simple message: Vote no!

The men and women — fighting to repeal a new ordinance restricting short-term rentals — were the public faces of Keep Our Homes, a campaign with legitimate grassroots elements but also nearly $5 million in funding from Airbnb.

The effort ultimately flopped: Some 70 percent of voters upheld the anti-Airbnb restrictions, which include capping short-term rentals where the owner isn’t present at 60 days per year.

The defeat marked another failed industry attempt to persuade politicians and the public. And although New York real estate interests shed few tears over Airbnb’s loss, they suffered their own stinging setbacks this year, notably on the proposed Amazon campus in Queens, rent reform and a New York City law establishing carbon-emission limits for large buildings.

“The real estate industry has to realize that their best hope is to have a vision and an agenda that will provide housing for working people,” said Mitchell Moss, a professor of urban policy and planning at New York University.

Don’t call them lobbyists

Lobbying derives its name from paid operatives hanging out in the lobbies of government buildings to snag face time with public officials passing through. But as an umbrella term used to describe both traditional and nontraditional methods of influencing policy, lobbying has been around for generations, comes in many flavors and changes as politics and culture do.

The word itself has over time become loaded, to the point that many firms in the business have scrubbed all mention of it from their websites and LinkedIn pages.

“I like to think of myself as an advocate, because that’s sort of the way I approach the work,” said Suri Kasirer, whose eponymous business regularly leads all firms in New York City lobbying revenue.

“I like to think of myself as an advocate, because that’s sort of the way I approach the work,” said Suri Kasirer, whose eponymous business regularly leads all firms in New York City lobbying revenue.

Despite the negative connotation of lobbying, business interests increasingly see it as essential. The $102.57 million paid to New York City lobbyists last year was 42 percent more than in 2014, according to the city clerk’s office.

“I also think it’s really important for people to understand [that], just like you wouldn’t go into a court without someone who knows how the courts work … generally you would want somebody who can help you understand the way government works, how you might approach folks in government,” Kasirer said.

Lobbying built on relationships in Albany has been unsettled by a leftward political shift that flushed out trusted political stalwarts and elevated a cohort of energized, organized tenant groups to the forefront of policy debates. In addition, new limits on campaign donations to political candidates have reduced the influence of real estate interests.

The shift has forced the industry to consider new strategies and alliances to build narratives that advance its agenda. But the Airbnb result in Jersey City proves that even a combination of corporate money and grassroots advocacy does not guarantee success.

Real estate and other industries use a variety of tactics to influence politicians and the public, beginning with hiring lobbyists, consultants and public-relations teams. These professionals — who tend to have worked in government and on political campaigns at some point — help arrange meetings with elected officials and orchestrate donations to their campaign accounts. They also design and place advertising, conduct robocalling and polling, send mailings to voters, ghostwrite and place op-eds, build coalitions, organize phone banks and rallies and testify at hearings and pack them with supporters.

Companies and trade groups also file lawsuits challenging government actions, but that is typically a last resort, even for the many attorneys in the lobbying business.

Jonathan Bing, who joined government-relations powerhouse Greenberg Traurig after representing a Manhattan district in the Assembly for nine years, said the firm takes a “lawyerly” approach to its work, weeding out any conflicts of interest before the client is signed. Next, it launches a research-heavy engagement that usually lasts at least a year, billed at a flat monthly rate, which the state’s lobbying database shows is generally several thousand dollars a month.

“When I was a legislator, I found that the lawyer lobbyists were very well prepared, especially when it came to thinking about what provisions should be in legislation,” he said. Bing noted that lobbying firms used to be mainly composed of attorneys — something that’s changed over the years.

Creating a narrative

Lobbying is, in many cases, an uphill battle. How to convince people that smoking doesn’t kill you? That sugar doesn’t cause diabetes? That plastic bags don’t harm the environment? In many cases, it comes down to storytelling — crafting a narrative that appeals to both political leaders and the public and placates people on both sides of the issue.

“My approach is to lay out a strategy and a plan with a client, and that plan might be multifaceted, so it will take into account what the goals are that we want to achieve, what is the messaging — how do we frame an ‘ask’ to folks in government — and an understanding of who might be for it and who might be against it,” said Kasirer. “Are there third-party stakeholders? Is there a grassroots set of folks that would support or oppose? And understanding why.”

For difficult sells, said Bing, it helps to bring in ordinary people to share their stories. “Elected officials count — they count the number of calls, emails,” the former legislator said. “I think with those more difficult issues, having grassroots make a difference.”

In 2013, facing a ban in New York City on plastic-foam food containers, the American Chemistry Council formed a group of small-business owners, known as the Restaurant Action Alliance, to advocate against the ban, claiming paper-based alternatives were expensive and ineffective. The plastic-foam industry also sent mailers to voters, cheering a City Council member who supported its position.

As a result, the bill was amended to make the foam ban contingent on a study proving the containers could not be realistically recycled. The bill passed but was overturned after a court battle in 2015 between Dart Container, a leading manufacturer of such products, and the city — because the courts found the city’s study fell short. Another study was conducted, and the ban came into effect in 2017. Although the industry’s campaign ultimately failed, it dragged out the process by four years, perhaps dissuading other localities from pursuing such legislation.

In another case, the New York City Hospitality Alliance, which represents restaurants, aligned with minority female restaurateurs from Harlem to stop the Cuomo administration from raising the minimum wage for tipped workers. The women testified at hearings, met with editorial boards and wrote op-eds, arguing that raising tipped workers’ base wage would force restaurants to raise menu prices and end tipping.

“Rather than take our employees’ gratuities, the governor should accept a tip from this group of successful minority and female business owners and save the tip credit,” the restaurateurs wrote in a 2018 op-ed about the issue. The wage board convened by Gov. Andrew Cuomo has yet to make a decision, and nearly two years after proposing the change in his State of the State speech, he rarely mentions the issue in public any more.

“Rather than take our employees’ gratuities, the governor should accept a tip from this group of successful minority and female business owners and save the tip credit,” the restaurateurs wrote in a 2018 op-ed about the issue. The wage board convened by Gov. Andrew Cuomo has yet to make a decision, and nearly two years after proposing the change in his State of the State speech, he rarely mentions the issue in public any more.

“When 20 female restaurant owners from Harlem publish an op-ed clearly explaining how eliminating the tip credit will hurt their small businesses and workers, in real life, politicians and the public rightfully pay attention,” said Andrew Rigie, executive director of the Hospitality Alliance.

Engaging with communities early is also important in lobbying for a major change. After Amazon dropped plans to build a huge campus in Long Island City, and after Airbnb’s defeat in Jersey City, both companies were criticized for coming in late, after their opponents had built up momentum against them. Amazon hired communications firm SKDKnickerbocker to advance its cause after protests began and just days before two of the tech giant’s executives testified at a City Council hearing. Both were pilloried.

Developer L&L MAG, in contrast, has spent the past year consulting with the community in Long Island City over a new plan at the site Amazon abandoned. Its CEO, MaryAnne Gilmartin, said at a panel event in November that her strategy of focusing on direct conversations with the neighborhood was informed by the Amazon fallout. “I think the lessons learned have helped us go back to Long Island City and say, ‘What has to be different?’” she said.

Large industries, including finance, tend to concentrate their lobbying in Washington, D.C., rather than in New York City and Albany. However, as New York’s City Council has grown increasingly aggressive toward business interests, many companies and trade groups are paying closer attention to city government and not relying on meeting with and donating to lawmakers to make their case.

The Real Estate Board of New York, for example, organized a rally on the steps of City Hall in June to oppose a City Council bill that would cap brokers’ commissions — galvanizing hundreds of brokers to show up in the hot sun, holding placards.

Reggie Thomas, the board’s senior vice president of government affairs, said the pushback helped create space for much-needed conversation and consultation over the bill. No vote has been held, and Thomas said conversations with the bill’s chief sponsor, Manhattan’s Keith Powers — a former lobbyist himself — were ongoing.

REBNY’s approach to Albany, however, has come under scrutiny since a landmark rent law passed in mid-June. For years, the group and its members bankrolled the campaigns of Senate Republicans, who reliably defended landlords’ interests but lost control of their chamber in the 2018 elections.

“REBNY spent millions for election causes, and it was a good strategy until it wasn’t,” said Bradley Tusk, a political consultant and former Michael Bloomberg mayoral campaign manager, observing that the board was blindsided by the rise of progressive politics after Donald Trump’s election. “The world changed, and they didn’t change with it,” he said.

In fairness to REBNY, its membership is far broader than owners of rent-stabilized buildings, who have been more traditionally represented by smaller landlord organizations. But those entities have virtually no political capital in the Democrat-dominated state legislature, leaving REBNY to carry the load.

NYU’s Moss argued that the trade group should remind the public that its members are not simply landlords, but the builders of the homes people live in, in the city they love.

In a nod to the changing landscape, the board is planning to hire a government-relations liaison to focus on Albany and another for the City Council, with the aim of building coalitions with groups that don’t carry the reputational baggage now saddling the real estate industry.

Despite the political shift, Bing said his firm’s approach to lobbying has not fundamentally changed. But the job has become harder. “Now you have to keep track of a lot more pieces of legislation and a lot more possibilities, because there are pieces of legislation that you never would have thought could pass a Republican Senate that might now pass the Democratic Senate,” he said.

Establishing a presence on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and the like has also become a standard component of advancing a political agenda. But Bing insists it will never be more important than actually showing up.

“One thing I do strongly recommend to my clients,” he said, “is regardless of how good you are at social media, having that personal relationship and taking that early-morning bus ride to Albany really does make a difference.”