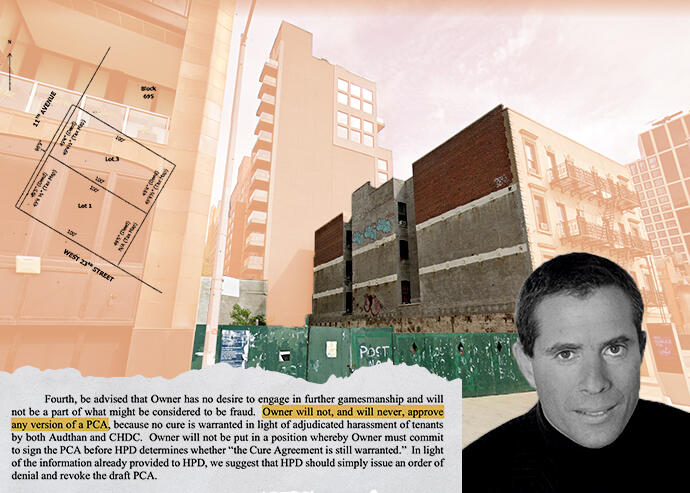

182-188 11th Avenue, CEO Jonathan Leitersdorf (New York State Supreme Court, ACRIS, BeachBox Ibiza, Google Maps)

A legal dispute blocking development of one of the last empty lots in West Chelsea has taken a dramatic twist.

After six years in court, mired in discovery and docket filings, Israeli financier Jonathan Leitersdorf appears ready to walk away from his long-planned development at 182-188 11th Avenue. But he doesn’t plan on leaving empty-handed.

The Leitersdorf company that signed an 88-year ground lease for the property, Audthan LLC, is now suing its landlord for breach of contract. It seeks at least $100 million in damages in an amended complaint filed Tuesday.

Audthan alleges that Gurdayal Kohly, an Indian immigrant who bought the property in 1979, has waged a “scorched-earth campaign” to stop the 58,000-square-foot project.

Construction has been frozen since 2009, when a judge found that a previous leaseholder had harassed tenants at the Chelsea Highline Hotel, a rent-regulated, single-room occupancy building at 565 West 23rd Street, on the developed half of the project site.

Consequently, Kohly was ordered to renovate the run-down hotel at the northeast corner of 11th Avenue and West 23rd Street into 15,000 square feet of permanently affordable housing.

One problem: Kohly’s not a developer. He doesn’t even own any other investment properties.

“Since I do not have — and indeed have never had — the capital to develop the land myself, I have always net-leased it,” wrote Kohly in an affidavit. “Net-leasing is the only viable option for me to be able to realize any profit from the property.”

Needing a development partner, Kohly in 2013 leased the property to Audthan for 40 years with an option to extend the deal for another 48. Though Audthan had not harassed the tenants, it was still obligated to execute a cure — an expensive proposition. But Leitersdorf had a plan to pay for the affordable units, make a profit and create a magnificent home for himself.

On the open portion of the land he would build Skybox Chelsea, a 250-foot building with luxury condo units and a five-story penthouse for his personal use. Reflecting contemporary Chelsea’s artistic sensibilities, the ground floor would feature an art museum and private gallery with 30-foot ceilings.

Almost immediately, the two sides fell out of step.

Kohly soured on the lease agreement, which established only modest rent increases for the ground he owned, according to Bradley Silverbush, an attorney for Kohly. It also failed to factor how profitable Skybox could be.

“He was taken advantage of,” said Silverbush.

While Kohly’s misgivings fermented, Audthan set about readying the site and preparing a harassment cure to unlock development rights. Audthan says it has spent $34 million on rent and project preparations.

But its cure application and development plan came under attack by an unexpected source: its own partner, Kohly.

For six years, the two sides have waged a legal war of attrition. They have argued before the court, cycled through lawyers, appeared before mediators and filed more than 1,000 items in the docket. And yet, the tract has proven intractable.

But a breakthrough appears imminent. This April, Kohly’s lawyer asked the Department of Housing Preservation and Development to reject Audthan’s proposed cure, which has languished in the city bureaucracy since December 2015. In his letter, Silverbush noted four tenant harassment lawsuits that Audthan failed to mention in its proposal, which he called a “sham.”

The next month, Silverbush sent the agency another email that would completely change the course of the lawsuit. “[Kohly] will not, and will never, approve any version of a proposed cure agreement, because no cure is warranted in light of adjudicated harassment of tenants” by Audthan and nonprofit Clinton Housing Development Company, the proposed administrator, he wrote.

This summer, after spending tens of millions of dollars and half a decade, it became clear to Leitersdorf that he would not be developing the land any time soon. So he threw in the towel on Skybox Chelsea.

On July 26, a Monday, his firm sent Kohly a letter saying it intended to surrender the premises, including responsibility for the SRO hotel, at the end of the week. Kohly saw the move for what it was: hardball.

“What are they gonna do?” his lawyer, Silverbush, said of his client. “Take over a hotel at 5 o’clock on a Friday with no management experience?”

Audthan’s amended complaint this week argues that Kohly repudiated the lease by vowing not to sign on to the cure agreement: If Audthan can’t execute the cure, it can’t build. And if it can’t build, its deal with Kohly is pointless.

But Kohly has his own card to play: In the lease, both sides waived the right to damages if either one fails to cooperate. So back to court they go.