NYC landlords feel that the city’s new energy efficiency grades do not reflect what’s going on at their buildings. (iStock)

Most people don’t like talking about bad grades. Including landlords.

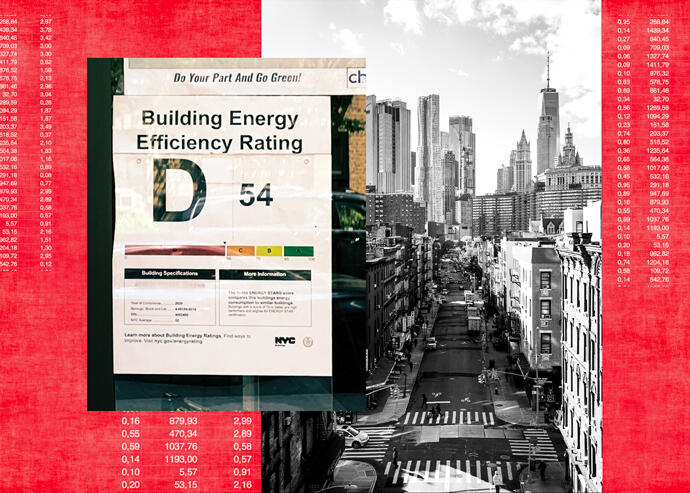

Last year, New York City began requiring letter grades based on energy efficiency and water usage to be posted on buildings over 25,000 square feet.

According to Department of Buildings data reviewed by The Real Deal, 43 percent of buildings received Ds, 15 percent received As and Cs and 16 percent received Bs. About 10 percent received an F, given to building owners who either did not publicly display their scorecard before Oct. 31, 2020, or failed to submit energy efficiency benchmarking.

Some landlords complained that the grades were an unfair characterization of their properties.

“It’s not giving an accurate picture of the efficiency of our buildings,” said Jordan Barowitz, vice president of public affairs at the Durst Organization.

The grades are calculated based on an Energy Star metric that compares the energy consumption of buildings across the country with similar density and use.

The buildings in Durst’s portfolio, which spans over 10 million square feet in New York, received a mix of grades. One of those that received a D is a prewar building that Barowitz said had recently been retrofitted with a brand new HVAC system and energy-saving windows.

“It runs extremely efficiently for the vintage building that it is,” said Barowitz. “Some older buildings are very lightly used and score fine, but that doesn’t mean they’re efficient buildings.”

Under the letter-grade statute, Local Law 95 of 2018, low scorers are not punished, as long as they participate. Building owners who receive an F are subject to a $1,250 fine, but buildings with Ds or better pay nothing. Starting in 2024, however, Local Law 97 — a different statute — will subject owners to a fine of $268 per ton of greenhouse gas emissions above a certain limit.

The energy-efficiency letter grades do not measure those emissions, which are Local Law 97’s domain. It is possible to receive a D grade and still be in compliance with Local Law 97 or receive an A grade and not be in compliance.

“I would be surprised if there are very many buildings that have gotten an A grade on their building and they would be subject to fines in 2024,” said Gina Bocra, chief sustainability officer at the Department of Buildings. “If you have a D, you may be facing fines in 2024, you may not.”

A building’s energy efficiency is only one component of its sustainability. Even the LEED Gold-certified Empire State Building received a mediocre energy-efficiency grade — a B.

The LEED program, a private initiative, proved popular because building owners use it to market their spaces and burnish their image. But if the idea of the letter-grade law was to shame building owners into making upgrades, it is hard to say if it is succeeding.

“Some people just aren’t affected by a bad grade,” said Tony Liu, a principal engineer at sustainability consultant Partner Energy Group. Liu said his clients are more concerned about Local Law 97 because non-compliance comes with heavy fines.

“LEED looks at a lot of different items,” he said. “Energy efficiency is one category out of many.”

The Real Estate Board of New York said its members are already investing in energy efficiency measures to achieve their own sustainability goals, improve their assets, retain and attract tenants and comply with the law.

“Local Law 95 and 97 present new precepts to their ongoing environmental efforts, which can be challenging given that LL95 is predicated on energy efficiency and LL97 is predicated on raw carbon emissions,” Alexander Shapanka, REBNY’s assistant vice president of policy, said in a statement. “Though energy efficiency is essential to limiting carbon emissions, the considerations for achieving Local Law 97 compliance go much further.”

Liu said many variables are associated with raising a building’s energy efficiency score but installing LED lights in common areas will not bring a D building up to an A.

“If you’re really going from a D to A, B or C, you’ll probably need to do some capital upgrades,” said Liu. Typically, that includes more costly upgrades like installing an energy-efficient HVAC system, reducing plug loads and purchasing efficient appliances.

Olayan Group’s 550 Madison Avenue, formerly known as the Sony Building, received an A grade last fall, but the 37-year old building had just undergone a $300 million gut renovation. “It’s really a brand-new building on the inside,” said Erik Horvat, head of real estate at Olayan America.

The Institute for Market Transformation (IMT), a nonprofit focused on energy efficiency for buildings, found that at the height of the pandemic, when office building occupancy dropped as much as 95 percent, only 5 percent of buildings experienced energy use reductions above 30 percent.

“Unfortunately there are a lot of buildings that are running their systems even when they’re empty and wasting a lot of energy,” said Cliff Majersik, a policy advisor at IMT.

The goal of Local Law 95 is to create public pressure to improve a building’s grade, similar to the food-safety grades posted on the front of restaurants.

Although that endeavor was successful, it is much more difficult for commercial buildings because restaurant consumers have more options.

“If they observe a D on the door of a restaurant, they probably want to go to the next restaurant where the grade is an A,” said Ginger Zhe Jin, a behavioral economist at the University of Maryland. “Maybe as an individual employee you just don’t have a choice of walking in or not walking in to that building.”

Peter Sabesan, a broker at Cresa, said that a building’s energy grade does not factor into a tenant’s decision to rent office space. Not one of his clients has ever walked away from a building because of its grade, he said.

“At the end of the day, it’s always about the rent,” said Sabesan. “If it’s an equal deal it’s definitely a plus, but if it’s not an equal deal, the tenants care about the rental package and the concession package more than the energy efficiency.”