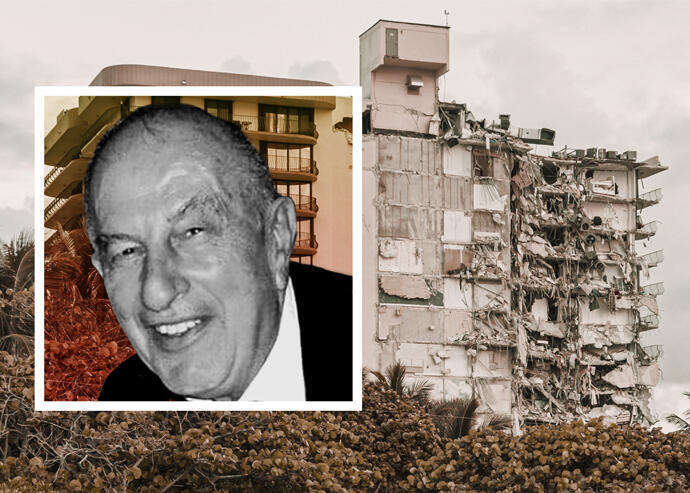

Nathan Reiber was the developer for Champlain Towers South in Surfside (Getty, Levitt-Weinstein Obituary)

UPDATED, July 19, 6 p.m.: As Nathan Reiber faced tax evasion charges and possible disbarment in Canada in the 1980s, he was already basking in a life of luxury in Miami Beach.

A few years earlier, Reiber started a new chapter as a prominent real estate investor and benefactor to the Jewish community and the arts, rubbing shoulders at posh fundraisers with the likes of Elizabeth Taylor. His reinvention followed a familiar narrative in South Florida: No matter what you do, if you have money and your business is successful, you will be embraced.

Among his notable projects was the Champlain Towers condo development, a three-building complex along the beach in Surfside.

But in the wake of the collapse of Champlain Towers South, the developer’s legacy is being re-evaluated. Rescue crews are still searching for victims in the cascade of rubble, with 97 confirmed dead.

The cause of the Surfside collapse remains under investigation, and no evidence has been found that Reiber and the rest of his original development team were to blame.

Reiber died in 2014 at 86 from cancer. He was described as a “sharp businessman” and as a “philanthropist” in his obituary in the Miami Herald.

Yet, news reports and documents dated decades ago show that Reiber had a history of legal problems and controversies.

“I always say people come to Miami for one of three things: for love, for a job or that they are running from something,” said Peter Zalewski, a Miami-based condo consultant.

Who was Nathan Reiber?

Born in Poland, Reiber moved to Montreal with his family in 1929 when he was 2 years old. He graduated from the University of Alberta law school and worked as an attorney in Toronto after being accepted into the bar in 1953.

Reiber dabbled in real estate, co-owning apartment buildings in Burlington, Ontario, where he was charged with skimming money from coin laundry machines in the apartment buildings. He failed to answer the charges in court, and a warrant was issued for his arrest in January 1981.

According to an Ontario Law Society document, Reiber allegedly evaded paying taxes and he and others were allegedly involved in making “false and deceptive” entries in the records of certain companies.

Reiber’s attorney admitted in front of a disciplinary committee for the Law Society that Reiber had failed to cooperate with the investigation into three tax charges. The committee allowed Reiber, who was not present at the hearing, to resign from the bar in 1984 with the understanding that he would not re-apply, according to records from the Ontario Law Society.

Years earlier, Reiber had moved to Aventura with the intention of retiring, according to his Miami Herald obituary. But those plans were short-lived.

In 1976, Reiber and another Canadian investment partner bought properties at 1040 South Shore Drive and 2021 Bay Drive in Miami Beach for a combined $200,000, Miami-Dade County property records show.

Reiber served on the boards of the Mount Sinai Hospital-Toronto, the YMHA and Miami Beach’s Temple Emanuel, according to his obituary. He also supported the University of Miami, Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami Beach and the Miami Jewish Health System.

He and his wife, Carolee Reiber, bought a nearly 1-acre lot on Star Island, one of Miami Beach’s toniest enclaves, in 1989 for $700,000, records show. The couple completed their two-story, seven-bedroom mansion in 1992, eventually selling it for $4.6 million seven years later.

Paul George, a local historian and former history professor at Miami Dade College, said he doubted locals knew of Reiber’s charges in Canada.

“He might have tried to ingratiate himself with Miami’s officialdom, the institutions that are important in the community,” George said.

Still, financial and legal trouble followed Reiber to South Florida.

It started off small in 1975, with GDG Cleaning Services filing liens for a total of $3,850 for unpaid landscaping work at three residential properties in Southwest Miami-Dade County that Reiber co-owned with others.

Then, from 1975 to 2009, three mortgage foreclosure lawsuits and five contract and indebtedness suits were filed against Reiber and his partners in real estate ventures, records show.

In one case, 8801 Collins Corporation — now tied to a resort across the street from the collapsed Surfside tower — sued Reiber, as well as his Champlain investment partners.

In another, William Friedmam, the architect of the Champlain Towers, sued Reiber and Centennial Towers, the previous name for Champlain Towers East, steps north of the collapsed tower.

Details of the suits remain unclear. The filings were labeled as “eligible for destruction” in 1993. William Friedman had dismissed his claim, and the court also dismissed the 8801 Collins case after all sides said they had resolved their dispute.

Carolee Reiber and Jill Meland, the Reibers’ daughter, did not respond to requests for comment.

Controversies

Reiber’s legacy project was the Champlain Towers in Surfside. Reiber and his development team started constructing Champlain Towers South at 8777 Collins Avenue in 1979 as the first of the three-tower complex along the oceanfront in Surfside.

It was a precarious time for South Florida. Miami Beach and Miami were in the midst of the Cocaine Cowboys era, when narco trafficking from South America proliferated. Time Magazine’s 1981 cover highlighted the wave of violence caused by the drug trade in an article titled, South Florida: Trouble in Paradise.

Miami Beach’s police force was overwhelmed also, as many Cuban refugees who arrived in the 1980 Mariel Boatlift had criminal backgrounds, according to Alex Daoud, a former Miami Beach mayor, who was later sentenced to prison on federal bribery charges.

“We had to increase our police department,” which had a force of 160, he said. “We eventually ended up with 400 people,” he said.

By most accounts, Surfside, just north of Miami Beach, was less impacted by crime. The small town mostly consisted of hotels and a small population of residents, many of whom had ties to Canada.

“Surfside at that time was single-family homes, relatively quiet, it was a modest community,” George said.

Yet, low-key, small Surfside had its turmoil, in part over a high turnover of town managers.

Mitchell Kinzer said that soon after he was elected Surfside’s mayor in 1978, the town fired the manager so quickly that Kinzer did not even have a chance to meet him.

It was just politics and “nastiness,” said Kinzer, who went on to serve for 22 years. “We had a group of people in town who used to try to run the government. They’d say, ‘Yes.’ You’d say, ‘No.’ They felt they were important, above the law and government.”

Reiber developed Champlain Towers South through his Nattel Construction company, in partnership with Champlain Towers South Associates, which was made up of 15 different LLCs, with differing ownership stakes. Reiber’s business partners were brothers Nathan and Isadore Goldlist, Kinzer said.

Kinzer, now 70, said the Goldlists were much more visible to him than Reiber.

“They were pretty down to earth,” Kinzer said of the brothers, adding that they were chicken farmers from Canada. “They were normal guys. They were kidding around.”

As Reiber began drawing up plans for Champlain Towers, Surfside was under a construction moratorium over sewer system issues. Reiber’s development team bankrolled half of the $400,000 cost to repair the sewers.

Champlain Towers South proceeded, but the plan for a 12-story condo was cringeworthy to locals.

“The idea of having a building that large in Surfside, to any of the people, was really not good, but bordering on horrendous,” said Seth Bramson, a long-time Miami historian who wrote a book on the history of Surfside.

In another round of contention over the project, the Champlain development team was accused of trying to buy favorable votes from the town council, according to a 1980 Miami Herald report. Joseph Miller, whom the Herald also identified as a project developer, had donated $100 to the campaign of one council member and $200 to another.

Miller then asked for the money back, telling the Herald the original plan was to donate to all 10 candidates. One of the council members agreed, but the other said he had spent the funds.

“It was highly controversial,” Kinzer said. “They caught a lot of heat for that.”

Still, the 136-unit building sailed through and was completed in 1981. Next came Champlain Towers North. Then the east tower, sandwiched between the two, was finished in 1994.

A place for starting over

Reiber was one of many businessmen who have faced legal or financial trouble elsewhere only to seek a new life in South Florida.

Among them is New York real estate player Yair Levy, who made a splash with condo conversions and amassed a $400 million empire.

Levy turned to downtown Miami after he was permanently banned from selling co-ops and condos in New York state.

A judge there determined that Levy had skimmed money from the reserve fund at one of his condo conversion projects for personal expenses.

That was in 2011. Now, he is completing a $50 million renovation of the former Metro Mall building in downtown Miami, which he rebranded as the Time Century Jewelry Center. It is expected to open in mid-2022. Istanbul-based high-end jewelry store Markaled will open its first U.S. shop there.

“The litigation was the result of the financial crisis during the Great Recession,” Levy said in a statement. “Prior to that period, I successfully completed developments that helped revitalize communities and brought landmark buildings back to life in New York.”

Shaya Boymelgreen was another prolific developer in Manhattan and Brooklyn. He partnered with diamond billionaire Lev Leviev in 2002. Amid the financial crisis, Boymelgreen was sued by lenders and condo residents, and left a trail of failed condo projects. This ultimately resulted in a ban from the New York attorney general in the offer or sale of securities, including condos, for two years.

His family has since had a few real estate deals in Miami Beach and Surfside. In Miami Beach, a company controlled by his wife, Sarah and son, Shmuel, and another relative, Menachem Boymelgreen, scored approval to build 49 residential units in Miami Beach before selling the project in 2017 for $31 million. In 2018, Menachem Boymelgreen secured a $23.5 million construction loan for a planned townhome project on Collins Avenue, between 93rd and 94th streets, in Surfside.

Like Reiber, they are rewriting their legacies after turning to South Florida.

“Miami is a place for starting over again,” said George, the historian. “So, you come here in many cases for a clean slate. And if you do well, in many ways you are elevated in people’s minds.”