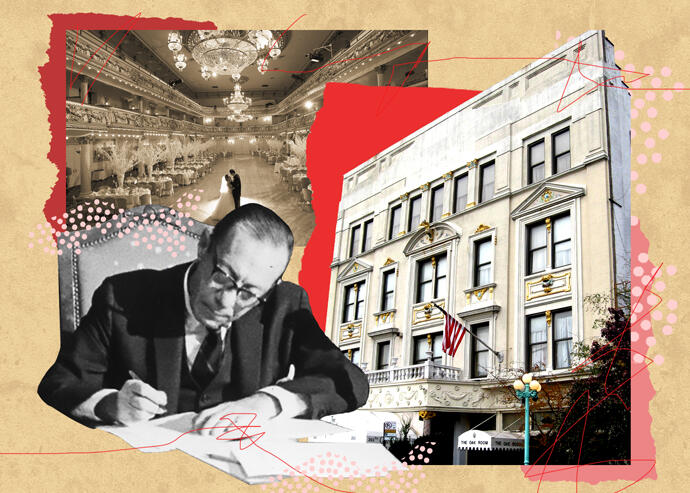

The Grand Prospect Hall at 263 Prospect Avenue with former Mayor Robert Wagner (Getty, Jim.henderson/Wikimedia, NYPAP/Illustration by Kevin Rebong for The Real Deal)

The Grand Prospect Hall is a Brooklyn landmark by any yardstick.

Its interior is decorated like a Trumpian fever dream, the Gilded Era frozen in time. It was enough of a cultural touchpoint that SNL spoofed its kitschy wedding commercial. Ordinary Brooklynites gathered like royalty in its cavernous hall for weddings, bar mitzvahs and more. It’s been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1999.

But its new owner, Angelo Rigas, doesn’t think it’s worth preserving. In July, the local electrician-turned-developer bought a 12-parcel assemblage on the edge of Park Slope that includes the hall. A month later, he filed plans to knock it all down. Rigas didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Once flattened, his properties, which measure 60,000 square feet — roughly the size of 13 basketball courts — could fit 120,000 square feet of residential or office space. It could yield a handsome profit in such a hot neighborhood.

But locals aim to stop the bulldozers. Two of them, Solya Spiegel and Toby Pannone, launched a Change.org campaign to halt the demolition. They argue that the hall is a borough icon, “the location where thousands of weddings, festivals, and concerts have taken place over its 129-year lifespan.”

Their silver bullet: get the city to landmark the building.

The pair quickly picked up support from elected officials, including City Council member Brad Lander and Assembly member Robert Carroll. As of Aug. 27, the petition had racked up more than 6,000 signatures.

But historic designation by the Landmarks Preservation Commission would not guarantee Grand Prospect Hall’s survival.

Contrary to popular belief, landmarking doesn’t actually spare a building from demolition, particularly if the owner is intent on its destruction. In the past five years, at least 38 landmarked buildings have received demolition permits according to an analysis of Department of Buildings and landmarks records.

And with $30 million invested in his assemblage, Rigas has little reason to play the philanthropist.

“No weapons, no hope”

In 1962, amid a postwar construction boom, Mayor Robert Wagner established the Landmarks Preservation Commission as a temporary, advisory panel to identify buildings and neighborhoods worth preserving. He was under increasing pressure from preservationists, who were frustrated by the city’s impotence in the face of developers razing New York icons.

Tensions came to a head in September 1964 when the New York Times reported that the Brokaw Mansion on the Upper East Side was slated for demolition. A scathing editorial by the Times’ architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable denounced the city’s failure to intervene and bemoaned the lack of recourse for preservationists.

“The wreckers and builders move in with the inexorability of the laws of economics, and the opposition, of those who would preserve the city’s past, have no weapons and no hope,” she wrote.

An adjacent news item on page L39 read, ironically, “City to Observe Landmark Week.” Together, the clips reflected the twisted fate of New York’s landmarks: In one second, love, in the next, a wrecking ball.

Mayor Robert Wagner signing the Landmarks Law (NYPAP)

In April 1965, just two months after the Brokaw Mansion was demolished, Wagner signed the Landmarks Law, creating a permanent panel with the power to designate individual sites and entire districts.

In July 1973, the Landmarks Preservation Commission waived its magic wand over 25 blocks — more than 1,800 buildings — to create the Park Slope Historic District. It was one of its first such designations, and only Greenwich Village’s historic district is larger. But the Park Slope district’s western boundary stopped a few blocks short of Grand Prospect Hall.

The commission has gained some influence in the years since, but its fundamental powers remain the same. Any building owner whose property lies within a historic district or is individually landmarked needs its approval for exterior renovations.

The hall’s would-be saviors can lobby the commission to designate their Prospect Avenue memento. But we’ve seen this movie before, and it’s unclear why this version would have a different ending.

Unresolved cases

The Grand Prospect Hall is a prime candidate for landmark status. It’s a distinct cultural icon, the type of building that carries weight with longtime residents and tourists alike. And the commission has been expanding its jurisdiction regularly. It now includes more than 37,000 properties including 1,400 individual landmarks.

Even the ruins of a smallpox hospital on Roosevelt Island are landmarked. Hell, a magnolia tree in Bed Stuy is landmarked.

Rigas’ plans would instantly be jeopardized by designation. As soon as the commission votes to approve a landmark, the building owner needs its approval for any serious exterior work. Rigas would have to present his demolition plans to Community Board 7, which would then advise the commission on whether to approve, modify or deny his plans. The body, whose 11 members are appointed by the mayor, would take the board’s decision and public testimony into consideration.

A demolition would require a full certificate of appropriateness, which can take up to 90 days and involves public hearings, a community board recommendation, and a commission vote.

But Rigas isn’t likely to face such hurdles. Activists would need to blaze through the lengthy designation process, enduring at least three public hearings and a historical review before even getting to the vote.

It’s a process so windingly bureaucratic that it borders on satirical: First, all 11 commissioners prepare comments. Then, the chair asks them to hold a public meeting, at which they decide whether to schedule a public hearing. It then punts to the relevant community board, who delivers its own report; in the meantime, the agency’s research staff writes a detailed report on the site’s cultural, historical and architectural relevance.

Finally, everyone’s opinion gathered, the panel holds its public hearing, where anybody can weigh in. The commission then votes, with a simple majority required for approval.

The group’s Aug. 21 request for evaluation still needs commission approval before even joining the agency’s list of possible landmarks. It isn’t on the docket for Landmarks’ next public meeting, Sept. 14.

And Rigas, the building owner, is moving quickly. He filed for his demolition permits nearly a month before activists’ landmark application. As of Aug. 28, he had erected a sidewalk shed and removed the hall’s awning, according to images shared by Save The Grand Prospect Hall. The city’s Department of Buildings does not show a permit for a shed.

Photos of the permit violation: pic.twitter.com/NGZ70NOxUQ

— Save The Grand Prospect Hall (@savethegph) August 28, 2021

Since 1998, Landmarks has had the authority to seek civil fines or even criminal penalties for owners who ignore it. But it tries to avoid exercising that kind of heft, issuing a warning and a violation before assessing any kind of penalties. And even when it does, it still has trouble getting owners to listen.

In April 2019, Dov Fischer bought the Elias Hubbard Ryder House, a landmarked 19th-century farmhouse near Gravesend. Three months later, he tore down its garage and began building a structure in its place, earning a stop work order from the Department of Buildings. Landmarks sent its own notice of violation in April 2020. Since July 2019, dozens of 311 complaints from concerned neighbors have piled up. Two years after Fischer began the unpermitted work, he owes at least $66,000 in penalties, city records show.

“Enforcement staff will do a new investigation into the current condition of the building and will take additional enforcement action if necessary,” said Zodet Negrón, a spokesperson for Landmarks, when asked why the case remained unresolved.

The commission has issued 3,590 violations since July 2014, and more than half of them remain uncured. Many are for small infractions, like replacing a door without approval.

But supporters have focused less on its 47 percent cure than on its ability to curb development and enhance property values — which critics see as contributing to the city’s affordable housing crisis.

An emerging body of research shows that in a tight housing market like New York, the choices the commission has made between aesthetics and affordability may need a second look.

Unintended consequences

In a paper published in the Journal of Urban Economics in 2015, researchers from Harvard, New York University and Georgetown examined residential transactions across 120 historic districts. They found that when those outside Manhattan received the designation, their property values increased and new construction fell relative to adjacent areas that did not.

Presumably this is because if the city makes development harder and more expensive, less of it will happen. The researchers stopped short of saying outright that landmarking limits housing supply, but did draw a conclusive link between designation and developers’ decisions to build.

In a study for Regional Science and Urban Economics, Yang Zhou, an assistant professor of economics at University of North Texas, found a stark connection between landmarking and the housing market in Denver. Sellers in historic districts there could expect a 12 to 23 percent premium. The boost even reached homeowners who lived near, but not in, an historic district. Their houses sold for up to 20 percent more.

And the impact goes beyond costs. Getting through the landmark permitting process requires time, money and professional help. “More expensive homes appear better able to take advantage of (or lessen the harms from) historic district designation,” Tetsuharu Oba and Douglas Simpson Noonan wrote in their study of historic landmarking in Atlanta.

The studies do not consider individual landmarks, like activists hope the Grand Prospect Hall will become. But such properties are subject to the same regulations as districts.

In many ways, Grand Prospect Hall represents all that the Landmark Law is supposed to protect: something beautiful, historic, and distinctly New York. But even if activists somehow landmark the building before it is razed, that protection can only go so far. The ghost of the Brokaw Mansion may soon have yet more company.