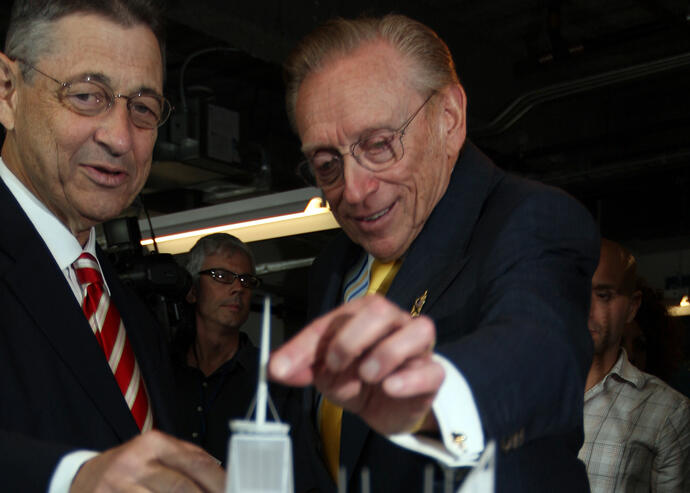

Larry Silverstein (Getty)

In July 2001, Larry Silverstein posed with a giant set of ceremonial keys to the World Trade Center — an iconic commercial complex that he’d long coveted and which hadn’t seemed within the reach of his small, family-run development firm. Just two months later, he was instead picking up the pieces at a site devastated by the worst terrorist attack in the nation’s history.

Silverstein moved quickly on what he saw as his “right and obligation” to rebuild all 16 acres of the World Trade Center site, a stance that often put him at odds with the various public agencies and officials involved with the redevelopment efforts. Lynne Sagalyn’s new book, “Power at Ground Zero,” recounts how plans for the site took shape –a winding road plagued by distrust between the redevelopment’s players and competing ambitions.

Sagalyn, who formerly headed Columbia University’s real estate program, paints Silverstein as an old-school developer, whose public persona oscillated dramatically during the decade-plus of rebuilding. In her telling, Silverstein was someone who sincerely wanted to rebuild Ground Zero as a lifelong New Yorker, a patriarch whose own employees died in the attacks. At the same time, she portrays him as a shrewd, opportunity-seeking businessman who maintained a “laser focus on the bottom line” during the entire rebuilding process.

“That sincere intent … did not change the developer’s deeply preconditioned approach to evaluating the risks of rebuilding from a business-as-usual perspective,” Sagalyn writes. “His interest was hard-wired to making money.”

Following the Sept. 11 attacks, Silverstein was singularly focused on rebuilding the full 10 million square feet of office space on the site, even as the city pushed to scale down the commercial portion of project. Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Deputy Mayor Daniel Doctoroff wanted 7 percent — or 700,000 square feet of space — to be set aside as residential in Towers 3 and 4 in order to speed up the construction timeline. The city also wanted to relieve Silverstein of his rebuilding responsibilities, often expressing doubt about his financial ability to follow through on the project.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey initially wanted Silverstein to go ahead with One World Trade Center and relinquish development rights to towers 2, 3 and 4, the most valuable of the properties from a real estate perspective. When Anthony Coscia, New Jersey’s appointed chair, told the developer in 2005 that they wanted to divide up the redevelopment work, Silverstein reportedly told him, “You’re a very nice young man and you probably have good thing in your future, but you’re very naïve. Have a nice day.”

Ultimately, Silverstein would keep the rights to 2, 3 and 4, and the Durst Organization would go on to develop the so-called Freedom Tower at 1 WTC. It’s been a struggle for Silverstein: In June 2016, 3 WTC finally topped out after about 15 years, and the developer is still trying to cobble together funds for 2 WTC.

In the chapter, “Larry’s Quest,” Sagalyn recounts Silverstein’s fight to maximize insurance proceeds to fund the rebuilding efforts. At the time, he employed public relations legend Howard Rubenstein — dubbed the “dean of damage control” by Rudy Giuliani — to promote his legal claim that the attacks qualified as two separate occurrences, rather than just one. The campaign painted Silverstein as a “plucky underdog” pitted against insurance companies and slow-moving bureaucracy, all while having the best interests of the city at heart. That narrative would compete with another that Silverstein pocket the insurance proceeds and walk away from the project.

Janno Lieber, who headed the World Trade Center redevelopment for Silverstein and is now the president of WTC Properties at the firm, said the book, at times, oversimplifies the motivations of the redevelopment’s key players. The book repeatedly refers to Silverstein as eternally optimistic and unwilling to leave a single dollar of his money on the negotiation table.

“What I think she underestimates is the degree to which some of us were thinking about this as a bigger picture, about how the new World Trade Center could fit into New York,” Lieber told The Real Deal. “Larry’s a business person, he’s a real estate person. But his interest was, how are we going to Create A Better Place?”

Sagalyn observes that Silverstein enjoyed leverage in the public-private partnership in that he had control of the site at the outset and controlled the insurance proceeds. Though the Port Authority considered — at least twice — taking over the project through eminent domain, to do so would’ve resulted in a legal dispute, a fact that Silverstein understood. The 99-year lease Silverstein inked in July 2001 for the World Trade Center didn’t account for a need to unwind the deal.

In response to the book’s assertion that Silverstein had the upper hand in negotiations with the Port Authority due to the July 2001 agreement, Lieber noted that they didn’t have much leverage since they were obligated to keep paying rent on the empty site and that they didn’t have the insurance funds in hand until 2007. He noted that government officials were taking a long time to decide what would happen to the sites.

“It wasn’t leverage but a little bit of a dose of reality,” he said of Silverstein’s position that the agencies needed to finalize a plan.

“Larry was the one who took a huge risk in building 7 World Trade Center on spec when others were not so confident about the future of Downtown,” Lieber added. “Larry was not looking to negotiate advantage. He was always looking to get something done.”

Sagalyn also poses the question: If Silverstein hadn’t already had control over the WTC site, would he have been selected to rebuild after the 2001 attacks? At the time, his firm didn’t have the same level of experience or liquidity as the largest development outfits in the city. He was the lead developer “by default.” (Not that he ever acted like it.)

“Extremely successful developers like Larry Silverstein possess something that not every developer has: an extraordinary degree of confidence in their own decisions and an opportunistic willingness to be contrarian and take enormous risks on upon that vision,” Sagalyn writes. “Taking on the risks of high-density development in the tough and competitive environment of Manhattan real estate requires Teflon resilience, an attribute Silverstein consistently demonstrated in his long career.”