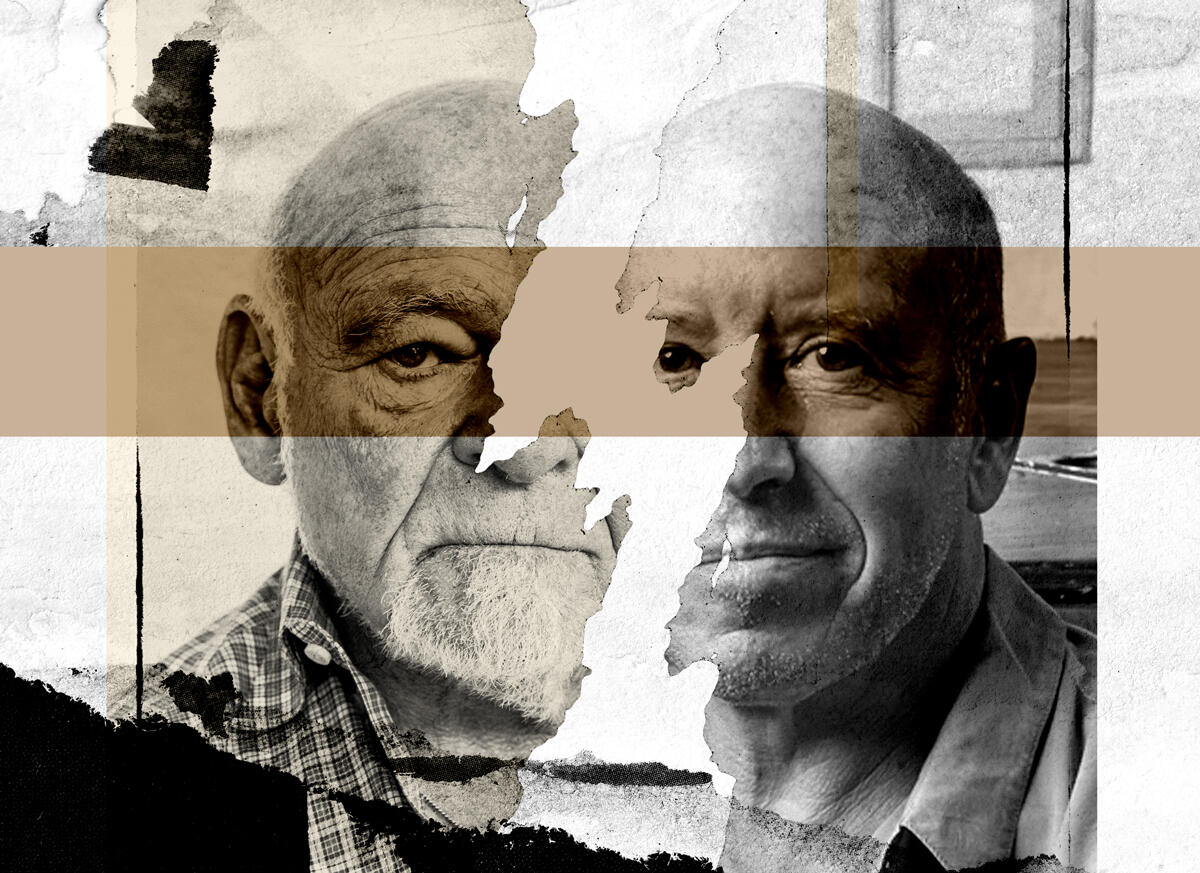

Sam Zell (left) and Barry Sternlicht (Photos by Studio Scrivo and Emily Assiran)

Sam Zell waited seven years to make his next billion-dollar move. Then Barry Sternlicht crashed the party.

The two real estate titans spent the summer locked in a $2 billion bidding war for Monmouth Real Estate, a family-run firm in a New Jersey suburb about an hour outside New York. At stake: Monmouth’s more than 120 warehouses across the country — property that surged in value as e-commerce usage skyrocketed during the pandemic.

“It’s been historically difficult to assemble portfolios in this space,” said Rob Stevenson, head of real estate research at Janney, a financial advisory firm. “This was a ready-made portfolio with a pipeline of deals included as well as infrastructure.”

Now Zell’s offer is dead in the water, Sternlicht’s is still in play, and Monmouth has hired Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, the New York law firm that hatched the idea of the poison pill defense, to explore alternatives.

The drama sheds light on how the industrial market, once an overlooked corner of the real estate world, became the next battleground for the biggest names in real estate. It’s also the tale of how Zell, the 80-year-old dealmaker who earned the moniker “grave dancer” to describe his habit of buying distressed portfolios, bungled an attempt to buy a healthy one instead.

Add to the mix accusations of cronyism, a bidding war and rebellious shareholders who fended off Zell’s approach even after it was approved by Monmouth’s board. Then there’s Sternlicht himself, an equally brash boardroom veteran who, at 60, is on the prowl for more deals.

Investor angst

The back-and-forth dates back at least to December, when Blackwells Capital, a New York activist investing firm led by Jason Aintabi, identified Monmouth as an underperforming REIT that was saddled with expensive debt and corporate governance concerns, including a board made up of friends and relatives of the founding Landy family.

Starwood Capital, Sternlicht’s firm, and Monmouth declined to comment. Zell’s Equity Commonwealth and Blackwells didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Monmouth’s board rejected Blackwells’ first all-cash offer, of $16.75 per share. About two weeks later, Blackwells raised its offer to $18 per share, a 21.6 percent premium to Monmouth’s stock price on Dec 1. Blackwells also said it would nominate four new board members to replace those tied to the Landy family, whose patriarch, Eugene, founded the company in 1968. Eugene Landy passed the CEO role to his son Michael in 2013, though he remains chair. Another son, Samuel, is also on the board.

“Monmouth cannot continue to be run under the jackboot of the Landy family,” Aintabi said in April, the month Blackwells filed preliminary proxy statements to nominate its board candidates. Aintabi is no stranger to boardroom duels: In 2019, he waged a three-month campaign to oust then-Colony Capital CEO Tom Barrack, only to end up settling with the company.

Yet by this April, Monmouth’s board had axed the offer from Blackwells, which by then held a 4 percent stake, and Zell and Sternlicht entered the fray. Zell had amassed a $3 billion war chest to fund his next big distressed move since taking control of office company Equity Commonwealth in 2014.

So few distressed opportunities turned up, even as the pandemic raged, that it was a telling moment when the investor with the morbid nickname turned his attention to logistics. Demand for industrial space has exploded in recent years, driving rents up 5.1 percent year-over-year in the second quarter to $6.62 per square foot, according to JLL.

“He started with that title, but he knows which way the wind is blowing,” said Jonathan Morris, a professor of real estate at Georgetown University.

By April, when Zell made his final offer, he apparently had Monmouth in the bag. He’d secured the vote of Michael Landy, as well as full support from the board. Zell needed only the backing of Monmouth’s shareholders, often a formality in corporate acquisitions. Equity Commonwealth even issued a news release announcing a deal to buy Monmouth for $3.4 billion in stock and cash that penciled out to $19.40 a share.

Zell said at the time the deal would give his company “a high-quality, net-leased industrial business with stable cash flows while preserving EQC’s balance sheet capacity for future acquisitions.”

But there were red flags.

Independent advisor Institutional Shareholder Services told shareholders to reject the Zell deal. ISS said Equity Commonwealth’s lack of experience acquiring logistics companies left “substantial uncertainty” that it would be able to build an industrial platform big enough to boost the price of stock it was offering to Monmouth shareholders.

There was another key mistake: Instead of spending his cash reserves, Zell’s offer was mostly stock — a move that would have allowed the Landy family to defer paying millions of dollars in taxes, even if it wasn’t necessarily the best deal for Monmouth shareholders.

Blackwells was outraged. The offer amounted to little more than a “tax shield” for the family, the firm said.

Sternlicht’s Starwood Capital touted its all-cash deal, saying that Equity Commonwealth’s own share price had fallen since the offer. It also took note of the board, saying half the members of the committee charged with evaluating the offer were corporate insiders. Echoing ISS, Starwood also said Equity Commonwealth had little experience in the industry.

As Zell’s deal awaited shareholder approval, Starwood raised its offer to $18.88, only to be rejected for a second time by Monmouth’s board, which stuck with Equity Commonwealth. Starwood upped its offer to $19.20 per share.

Starwood’s pitch resonated with investors. In August, they turned down Zell’s offer. Michael Landy said he was disappointed by the outcome, although he acknowledged concern shareholders had about tax issues. Starwood’s offer is still pending, though it hasn’t been scheduled for a vote.

Now, with the failed deal receding into the past, pressure is mounting to liquidate Equity Commonwealth and return its cash to shareholders. That’s not as extreme as it sounds: After all, the company has sold all but four of the 120 companies it once owned and exists primarily to put to work the money that it raised. Besides, its investors may be growing restless, said Danny Ismail, an analyst at Green Street Advisors.

“The shareholders have been waiting for several years now,” he said. “The longer it goes on, it begs the question, `Why not just return the capital to shareholders?’”

Sternlicht, meanwhile, is lining up his next move. Starwood, which sold all but eight of its 30 shopping malls during the pandemic, raised $9 billion by June for a fund that will target distressed opportunities worldwide.

And Monmouth? It may soon be back in play. If the company heads back to the market, some analysts say, it could gain even more attention, given the industrial sector’s explosive growth.

“Things have only become more and more expensive,” said Stevenson, the Janney analyst. “It could wind up being more bidders at a higher price if the company was marketed today.