In 2014, Oceanwide Holdings announced plans to build a 2.4 million-square-foot megaproject in San Francisco. The twin-tower development would be the Chinese conglomerate’s first big push into North America, at a time when Chinese firms were spending billions on massive projects and on acquiring high-end properties from California to New York.

In 2014, Oceanwide Holdings announced plans to build a 2.4 million-square-foot megaproject in San Francisco. The twin-tower development would be the Chinese conglomerate’s first big push into North America, at a time when Chinese firms were spending billions on massive projects and on acquiring high-end properties from California to New York.

Seven years later, the stalled project — dubbed Oceanwide Center — has come to represent something else: a $1.6 billion burden. Another is a massive L.A. tower project where work has also stalled, along with two large-scale developments still in the planning stages in New York City and Honolulu.

“If you drive around any major city in China you will see a handful of unfinished construction projects in various stages of completion,” said a construction project manager who requested anonymity, citing ongoing litigation with Oceanwide. He said those properties can sit empty for years. “Who says the same thing can’t happen here?”

Oceanwide — whose businesses include financial services, technology and power plants — has also been battered by lawsuits in the U.S. and in China, a recent bond downgrading and capital controls from Beijing that have tightened the belt on investment abroad.

In January 2020, Oceanwide said it would be divesting its San Francisco project — which would be the city’s second-tallest building — citing economic shifts at home and abroad, which had put pressure on the company.

By the company’s own estimates, the planned $1 billion sale of the project to Beijing-based asset manager SPF Group would have represented a near-$280 million loss. But several coronavirus-related delays scuttled that deal as well as a subsequent one with another China-based company, the private equity firm Hony Capital.

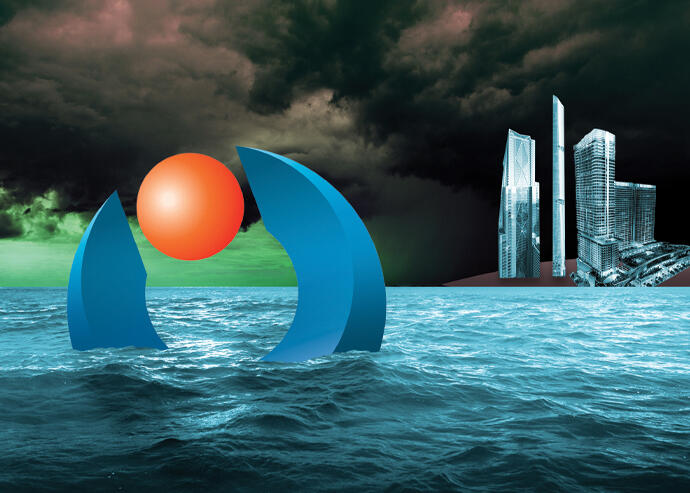

Oceanwide now appears adrift, trying to shed its U.S. properties as it seeks to exit real estate. But facing a cash flow crunch in China and with ratings agencies having downgraded its bonds, is it too late to right the ship?

Oceanwide did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Crashing wave

Under the leadership of billionaire Lu Zhiqiang — who stepped down as president and CEO last year but remains the firm’s majority shareholder — Oceanwide rode China’s real estate wave over the past three decades to become one of the country’s largest private business groups.

But trouble has been looming, according to Wei Du, a reporter with Wuhan-based Changjiang Times. “In the face of massive debts, Lu Zhiqiang has resorted to the typical self-rescue methods — disposing of assets and bringing in ‘strategic investors’,” Wei wrote in April. “After selling land parcels and shares in Minsheng Securities, Oceanwide has already recovered tens of billions [of yuan] — which isn’t enough to quench its thirst. And there has been no visible progress in attracting strategic investment.”

Around the time the company was making inroads into U.S. real estate, it also started a strategic repositioning that would see financial services become the main focus of its business. This shift was formalized in early 2020, when Chinese securities authorities reclassified its Shenzhen-listed holding company as a financial firm rather than a real estate firm. According to its 2020 earnings report, just 15 percent of its $2.2 billion in income over the previous year came from real estate. Most of the remainder came from financial services, through subsidiaries like China Minsheng Trust, Minsheng Securities and Asia-Pacific Property and Casualty Insurance.

Within China, the group’s ongoing real estate developments are mainly concentrated in the central business district of Wuhan, where Covid-19 was first discovered and which bore the brunt of the pandemic early on.

Oceanwide’s other interests include a pair of coal-fired steam power plants in Sumatra, Indonesia, and U.S. technology media firm International Data Group, which it acquired in 2017 for an unspecified sum and then sold to Blackstone Group earlier this month for $1.3 billion.

For the past several years, Oceanwide was also party to one of the longest-running “zombie deals” ever, as it struggled to line up funding and regulatory approvals for a $2.7 billion acquisition of U.S. insurer Genworth Financial.

That deal finally fell apart in April, when Genworth exercised an option to terminate the merger, with plans to possibly pursue a partial initial public offering instead.

Lightening the load

In late 2019, reports emerged that Oceanwide was seeking to sell off not only Oceanwide Center in San Francisco, but also Oceanwide Plaza in L.A. and its development site at 80 South Street in Lower Manhattan, where it planned to build a 1,400-foot-tall mixed-use skyscraper. The company’s land holdings in Hawaii, where it planned a high-end resort, were not up for sale at the time.

Oceanwide did manage to dispose of one of its U.S. properties last year, selling a 358-acre Sonoma Valley site in California to Ron Burkle’s Yucaipa Companies for an undisclosed sum. An Oceanwide subsidiary paid $41 million for the site in 2014 and secured approval for a 50-room hotel, spa and restaurant.

If last year’s will-they-or-won’t-they saga with Hony Capital is any indication, selling off the stalled San Francisco and L.A. projects will not be easy — especially as Oceanwide hopes to maintain naming rights and some control of the projects, sources said. Even as the impact of the pandemic subsides, the projects remain mired in lawsuits.

While several buyers reportedly expressed interest in Oceanwide Center early this year, a deal has yet to materialize. Meanwhile, in May, Swinerton Builders and Webcor Construction — contractors on the San Francisco project — sued Oceanwide over a mechanic’s lien of more than $108 million.

In L.A., legal wrangling at Oceanwide Plaza has dragged on since early 2019, with mechanics’ liens on that project now totaling more than $240 million. And it’s not just construction firms that are suing to get paid.

EB-5’s swirling currents

In February, a group of eight Chinese EB-5 investors sued Oceanwide Plaza’s senior credit line lender, L.A. Downtown Investment LP, over alleged mismanagement of their investment in the project. Oceanwide is not a party to the suit, although the filing did result in a notice of legal action being placed on the property.

While 273 EB-5 investors provided a total of $136.5 million for the Downtown L.A. mixed-use project, Oceanwide had difficulty securing the additional funding it needed, court filings show. This was partially due to the actions of the investors’ LP itself, which refused to subordinate the EB-5 money to a new bridge construction loan

Around April 2020, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services had begun denying investors’ EB-5 petitions because it had determined the project had stopped, according to the lawsuit. In September, Oceanwide allegedly missed a $5 million payment to investors, putting the loan in default.

The EB-5 suit has caused further problems with Oceanwide Plaza’s financing. “The lawsuit prevented Oceanwide’s new potential lender and the lender’s title insurance company from completing their due diligence for the loan closing,” the developer’s lawyers wrote in a May joint status report.

Despite the termination of that deal, Oceanwide says the lender is still prepared to close — no earlier than August — provided that the developer settles its many suits with subcontractors.

The project’s contractors are less optimistic.

Despite claims to the contrary, “it does not appear that Oceanwide has made progress in closing on said loan,” Webcor’s lawyers wrote in the same status report.

And in an ominous note, Oceanwide said it now believes that the L.A. project’s “valuation amount is insufficient to cover the costs incurred,” according to a filing on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

Setting a new course

How Oceanwide handles its two California megaprojects will help determine whether it can deal with pressures on its other businesses.

Last month, Chinese rating agency Golden Credit Rating International downgraded the company twice, from AA+ to AA- to A with a negative outlook, citing a number of concerning events.

Among them was Oceanwide’s disclosure in April that a Wuhan court had frozen several of its real estate assets in the city in connection with various legal disputes.

In May, the company announced it had refinanced $146 million out of a total $280 million in debt that had come due, while the remainder of that debt would be extended to August — further highlighting its looming debt obligations.

“Due to the adverse impact of a number of factors including the macroeconomic environment, the regulations on real estate and financial industry and the Covid-19 pandemic, Oceanwide Holdings … is facing a temporary cash flow issue,” the company’s Hong Kong subsidiary disclosed at the time.

Funds for debt repayment would be raised from “expedited sales of real estate projects” and “intended disposal of certain offshore assets,” the disclosure continued.

In the meantime, Oceanwide’s projects in L.A., San Francisco and New York are still on pause and there is no timeline for the Honolulu development.

“We always thought [Oceanwide] was circling the drain,” said the construction project manager, referring to the San Francisco sale in limbo and the scuttled Genworth deal. “It looks like the circles are getting smaller now.”